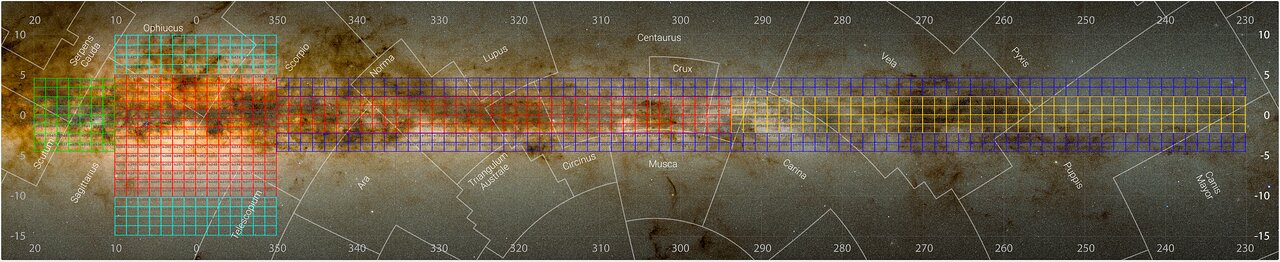

It took more than 13 years and it has more than 500 terabytes of data, but the most detailed infrared map of our galaxy has now been completed. The project was the largest ever conducted by the European Southern Observatory, featuring over 200,000 images snapped by VISTA – the Visible and Infrared Survey Telescope for Astronomy at the Paranal Observatory in Chile.

It’s difficult to do infrared astronomy from the ground, so the telescopes are positioned at high altitudes and where there is very little humidity. The previous map, published in 2012, has one-tenth of the objects. This new follow-up embraces the power of infrared to the max. Using these wavelengths, the team saw through the dust that shrouds the plane of the Milky Way, as well as seeing cold objects, such as brown dwarfs and free-floating planets that have been kicked out of their star systems.

“We made so many discoveries, we have changed the view of our galaxy forever,” Dante Minniti, an astrophysicist at Universidad Andrés Bello in Chile who led the overall project, said in a statement.

This is not an overstatement. Since the project began in 2010, over 300 scientific articles have been published based on the observations. Crucial to those was the data coming from the VISTA Variables in the Vía Láctea (VVV) survey and its companion project, the VVV eXtended (VVVX) survey. Via Lactea is the Latin name for the Milky Way.

Measuring variable stars is crucial to creating the 3D aspect of this map. Certain variable stars have a very precise relationship between the period it takes to brighten and dim and their intrinsic luminosity. From Earth, we can only measure their brightness – how dim they appear being so far away. But if we know the exact luminosity and measure how dim they appear to us, we can work out how far away they must be.

This relationship, understood first for Cepheid variables by Henrietta Swan Leavitt, is key to working out the distances of very distant objects. And so the VISTA map is not just about the location of these objects in the sky, but how far or close they are to us.

“The project was a monumental effort, made possible because we were surrounded by a great team,” said Roberto Saito, an astrophysicist at the Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina in Brazil and lead author of the paper.

All this information will provide data that will be used and analyzed for decades to come. And it will be crucial for the proposed follow-up to another galaxy mapmaker: Gaia. There is currently a proposal to do the next iteration of Gaia in an infrared observatory.

The study is published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

![An artist’s concept looks down into the core of the galaxy M87, which is just left of centre and appears as a large blue dot. A bright blue-white, narrow and linear jet of plasma transects the illustration from centre left to upper right. It begins at the source of the jet, the galaxy’s black hole, which is surrounded by a blue spiral of material. At lower right is a red giant star that is far from the black hole and close to the viewer. A bridge of glowing gas links the star to a smaller white dwarf star companion immediately to its left. Engorged with infalling hydrogen from the red giant star, the smaller star exploded in a blue-white flash, which looks like numerous diffraction spikes emitted in all directions. Thousands of stars are in the background.]](jpg/jet-m.jpg)