The great thing about having telescopes that can look further and further into the past is being surprised by what we see there.

With the infrared JWST, we were hoping to learn more about the formation of galaxies, as well as clear up mysteries about how supermassive black holes became so large. But we have been thrown a few surprises as we look further back into the past.

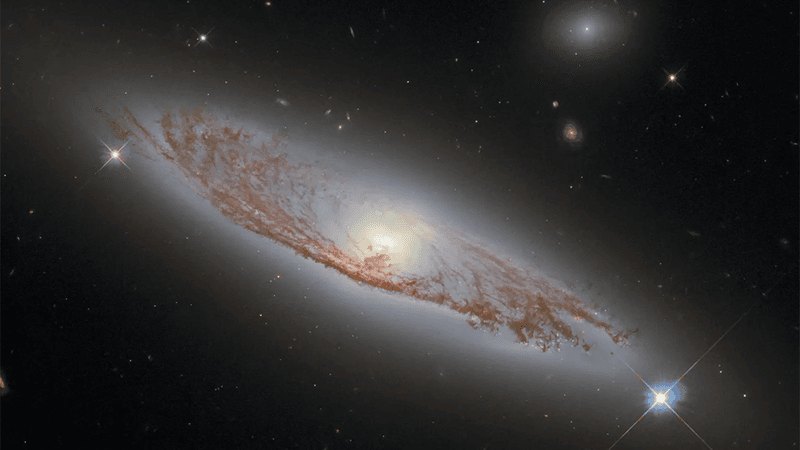

One such mystery has been thrown up by the galaxy JADES-GS-z13-1-LA, located around 33 billion light-years from us. This galaxy has a redshift of 13, which is a measure of how much a galaxy's light has been stretched by the expansion of the universe. A redshift of 13 means that the light from the galaxy has been traveling to us from about 330 million years after the Big Bang.

There are older galaxies which we have observed, but this one turns out to be particularly weird. What makes it so strange are its spectra, which showed a large spike in Lyman-alpha, or the hydrogen emission line. While stars are made of hydrogen – so this might not seem too weird – this is an emission line we were not expecting to see this early in the universe.

"This is WILD. This is an 'emission line' from hydrogen gas, where an electron drops down an energy level and gives off a photon of a specific ultraviolet energy," astronomer Kevin Hainline, author on the new paper, which has not yet been peer reviewed, explained on X (Twitter).

"This emission is seen often in *nearby* galaxies. But as we go back in time, we find that the universe had a period where it was very opaque to ultraviolet radiation. The universe changed from opaque to translucent over a period of a billion or so years, as the first stars and quasars 'reionized' the hydrogen gas everywhere."

During the cosmic "dark ages" the universe was filled with a thick "fog" of this hydrogen, which gradually cleared as stars and galaxies formed. By redshift 6, around 12.716 billion years in our past, astronomers believe that this process would have been complete. But before then, ultraviolet light should be more and more difficult to see, as it would be obscured by more and more hydrogen stripped of its electrons.

"Seeing the line at REDSHIFT 13 is INSANE, everyone," Hainline continued. "It's so shocking that when we saw it in our JADES data it almost took the focus away from our confirmation of JADES-GS-z14-0, because it was so unprecedented. How is this light finding its way to us through the opaque universe?"

Unfortunately, we do not have an explanation of why this galaxy's hydrogen emission line would be visible so early in the universe. Astrophysicists have been quick to point out that Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND) predicts that reionization would take place earlier than the standard model suggests. However, it is a little early to suggest new physics, with the team suggesting that an accreting supermassive black hole and associated ionization cone may offer an alternative explanation for the broad Lyman-alpha line.

For now, we will have to wait for further observations of the early universe for more clues to what is going on here.

The study is posted to preprint server arXiv.

![An artist’s concept looks down into the core of the galaxy M87, which is just left of centre and appears as a large blue dot. A bright blue-white, narrow and linear jet of plasma transects the illustration from centre left to upper right. It begins at the source of the jet, the galaxy’s black hole, which is surrounded by a blue spiral of material. At lower right is a red giant star that is far from the black hole and close to the viewer. A bridge of glowing gas links the star to a smaller white dwarf star companion immediately to its left. Engorged with infalling hydrogen from the red giant star, the smaller star exploded in a blue-white flash, which looks like numerous diffraction spikes emitted in all directions. Thousands of stars are in the background.]](jpg/jet-m.jpg)