When chemists had an idea for a better catalyst to make ammonia, they decided to try nine variations at the same time. That turned out to be just as well, because the version they expected to work didn’t – but one of the long-shot alternatives proved so successful the work could end up cutting carbon emissions equivalent to those of a medium-sized country.

Modern food production depends on ammonia-based fertilizers, without which billions would have starved long ago. However, the Haber-Bosch Process, the method developed over 100 years ago to produce ammonia from nitrogen and hydrogen, is immensely energy-intensive, requiring high temperatures and pressures. Ammonia production is responsible for around 2 percent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. That might not sound like much until you realize it’s more than Germany's – or indeed any country outside the top five – and not far off all air travel.

Naturally, finding a better way has been a top priority for chemists for decades, but even promising-looking solutions have so far not turned out to scale. When liquid metal catalysts started proving useful for other reactions around 2016, a team including senior author, RMIT University’s Professor Torben Daeneke, thought they’d take a shot at the biggest game in town.

Daeneke told IFLScience that they; “Started off with gallium because it has a low melting point and is non-toxic and safe to work with, making it a good replacement for mercury.” Gallium alone proved a poor catalyst for ammonia production, but the team had a hunch that doping it with a transition metal might work better.

The team expected iron to be their best chance, since it has already been shown to work as an ammonia catalyst, but tried nine other transition metals for comparison. Daeneke told IFLScience; “We decided to go cheap, avoiding metals like platinum.” That choice made any product easier to bring to market, and helped stretch the research grant a bit further.

The team had no reason to think copper would work, given its demonstrated lack of success as an ammonia catalyst, but included it for completion. To their surprise, the gallium-iron catalyst failed, but gallium-copper could be just what the world needs.

“Liquid metals allow us to move the chemical elements around in a more dynamic way that gets everything to the interface and enables more efficient reactions, ideal for catalysis,” Torben said in a statement. They also avoid becoming deactivated by side reactions.

Daeneke explained to IFLScience that the products of side reactions stick to traditional catalysts and rapidly reduce their effectiveness, but with liquid versions; “They have nothing to grab onto.” However, Daeneke added it is now becoming clear that liquid metal catalysts are not just more powerful versions of their solid counterparts; they can also be quite different. This means that sometimes a liquid version will work even when a solid one does not.

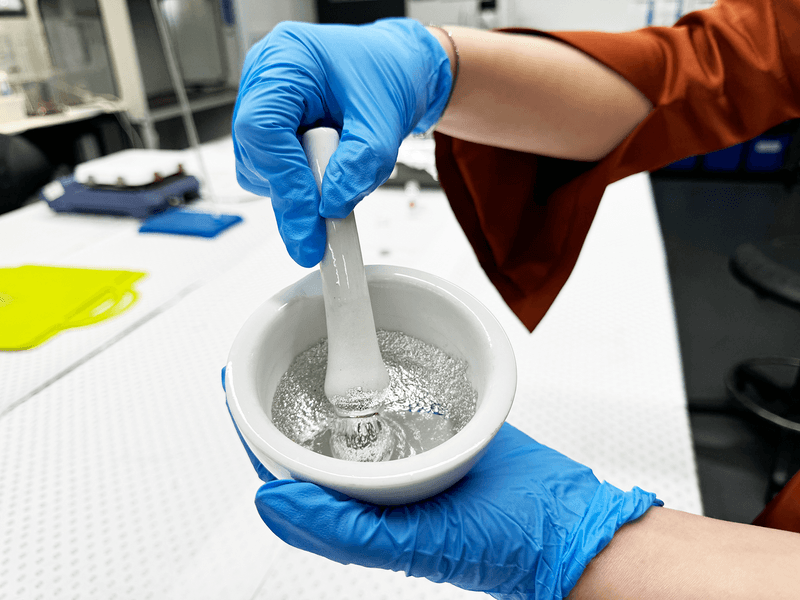

When gallium and copper are ground in a handheld device and then exposed to sound waves at 400°C (750°F), tiny droplets form. The team calls these “nano planets” because, like Earth, they have a hard crust over a liquid outer core and solid inner core. When placed in a mix of hydrogen and nitrogen, the hydrogen initially removes the oxidized crust, producing a little water: then the ammonia formation starts. The copper breaks up the hydrogen molecules while the gallium splits the nitrogen, allowing the two to combine.

Even with this preparation, gallium-copper liquid catalysts are vastly cheaper and more environmentally friendly than the precious metal ruthenium, which is currently used.

More importantly, the process uses 20 percent less heat, and 98 percent less pressure than the Haber-Bosch process, slashing the energy consumption and associated carbon emissions.

Daeneke told IFLScience the system should be easy to implement widely because it can be applied in existing ammonia-making facilities with little change. However, there is also potential for it to be used in much smaller reactors where the Haber-Bosch process is uneconomic. This could allow ammonia to be produced more locally. Australia, where Daeneke is based, recently had one of its major highways blown to smithereens when a tanker carrying ammonium nitrate crashed, so reducing the need for transport could improve safety, as well as saving money.

For all the dangers, ammonia is still easier to transport than hydrogen, and could be used as a storage mechanism for hydrogen produced in times and places where renewable energy is cheap. With the right process, demand could rise.

So important is finding a low-emissions path to ammonia production that chemists aren’t just taking inspiration from villainous robots in science fiction films. The same edition of the journal Nature Catalysis that this paper is published in also has one on using E. coli to achieve the same outcome.

![An artist’s concept looks down into the core of the galaxy M87, which is just left of centre and appears as a large blue dot. A bright blue-white, narrow and linear jet of plasma transects the illustration from centre left to upper right. It begins at the source of the jet, the galaxy’s black hole, which is surrounded by a blue spiral of material. At lower right is a red giant star that is far from the black hole and close to the viewer. A bridge of glowing gas links the star to a smaller white dwarf star companion immediately to its left. Engorged with infalling hydrogen from the red giant star, the smaller star exploded in a blue-white flash, which looks like numerous diffraction spikes emitted in all directions. Thousands of stars are in the background.]](jpg/jet-m.jpg)