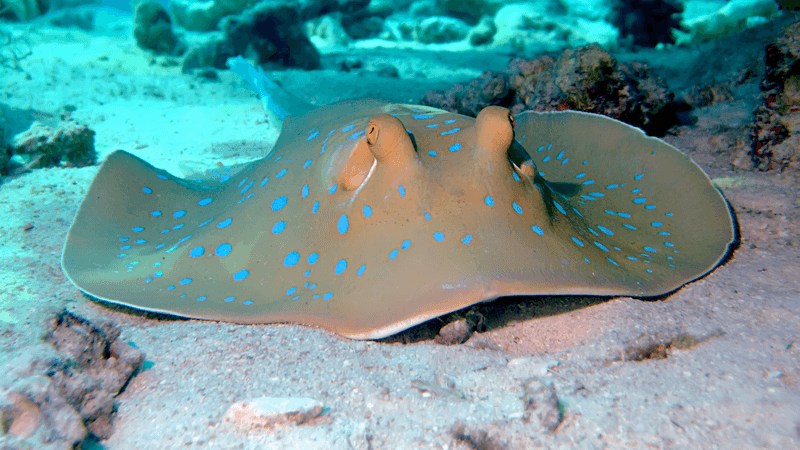

The mystery of how the bluespotted ribbontail ray got its blue spots has been solved by a team of scientists, yielding what they described as a “surprising and fun solution to the stingray colour puzzle.” Their investigations revealed that the electric blue comes not from pigment, but extremely small structures that influence the way light behaves.

Blue is rare in nature, and in the case of the ribbontail ray, it’s even more interesting as the color doesn’t change depending on the angle you look at them from. The ray species, known to science as Taeniura lymma, therefore landed itself a spot alongside the blue shark (Prionace glauca) as a candidate for studying the rare occurrence of brilliant blues out in the wild.

The team used microcomputed tomography (micro-CT), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) to take a close look at the architecture of the ribbontail ray’s skin. Surprisingly, what they saw reminded them of *checks notes* bubble tea…

“We discovered that the blue colour is produced by unique skin cells, with a stable 3D arrangement of nanoscale spheres containing reflecting nanocrystals (like pearls suspended in a bubble tea),” said visiting academic at Trinity College Dublin, Amar Surapaneni, in a statement. “Because the size of the nanostructures and their spacing are a useful multiple of the wavelength of blue light, they tend to reflect blue wavelengths specifically.”

As for how their bubble tea skin was pulling off that Mona Lisa trick, it seems the unique “quasi-ordered” arrangement of the nanoscale spheres Surapaneni mentioned were the key.

“And to clean up any extraneous colours, a thick layer of melanin underneath the colour-producing cells absorbs all other colours, resulting in extremely bright blue skin,” added Mason Dean, Associate Professor of Comparative Anatomy at City University of Hong Kong. “In the end, the two cell types are a great collaboration: the structural colour cells hone in on the blue colour, while the melanin pigment cells suppress other wavelengths, resulting in extremely bright blue skin.”

Such electric blue coloration might seem a little showy for an animal that's pretty much designed to blend into the sand, but the blue dots probably are actually an effective camouflage in a marine environment. Blue penetrates deeper than any other color in the ocean, and since the ray’s blue spots don’t change depending on the angle, there’d be no reason for any onlooking predators to suspect a meal is passing them by. Using nanostructures to create such vivid colors is a neat magic trick, and one seen across many species, from tarantulas to peacocks.

“If you see blue in nature, you can almost be sure that it’s made by tissue nanostructures, not pigment,” said Dean. “Understanding animal structural colour is not just about optical physics but also the materials involved, how they’re finely organized in the tissue, and how the colour looks in the animal’s environment. To draw all those pieces together, we assembled a great team of disciplines from multiple countries, ending up with a surprising and fun solution to the stingray colour puzzle.”

Solving the puzzle may also inform the creation of novel biomaterials. In fact, the team have already taken inspiration from the stingray’s soft skin to begin creating a flexible biomimetic structurally-coloured system that could one day be applied to flexible displays, screens, and sensors.

Thanks for the head start, ribbontail ray.

The study is published in Advanced Optical Materials.