The year is 2075. The place: the Neil Armstrong International Lunar Base in Henson Crater, some 30 kilometers (19 miles) southwest of the moon’s South Pole. Chinese electrical engineer Liu Mei and American astronomer David Scott IV sit side by side inside a pressurized, six-wheeled, fuel cell-powered lunar transporter. They have just exited the station’s car airlock and are rolling down the Moon highway made of laser-baked lunar dust towards the 1-kilometer (0.6-mile) high crater rim to the south.

The waxing blue marble hangs above the ominous mountains on the horizon, the familiar outline of Africa clearly discernible, as they begin their expedition. It will be a long day. Their destination is Shackleton Crater, some 50 kilometers (31 miles) away, site of the recently deployed Lunar Crater Radio Telescope, which has been reporting glitches and needs a checkup.

They pass a new greenhouse, around which a swarm of solar-powered, 3D-printing robots bounce on the uneven terrain in the weak lunar gravity, digging up lunar dust that will be used to build a thick shell around the inflatable module to protect it from micrometeorites and cosmic radiation.

In the distance, a field of solar panels gleams in the early lunar morning sunlight, sending life-sustaining electrical power to the base through a wireless microwave system.

All of that, at this stage, is just a fantasy. But Moon exploration proponents are convinced that 50 years from now, the Earth’s natural satellite will no longer be just a desolate celestial sphere. The Moon in 2075, experts think, will host at least one permanently inhabited lunar station, similar to those scattered across the frozen Antarctic today. The more optimistic Moon settlement enthusiasts expect that by 2075, the first babies may have been born on the Moon, proving (or disproving) that humankind as a species can survive without our mother Earth.

The case for the Moon

Italian space policy adviser Giuseppe Reibaldi is one of those Moon settlement optimists. A self-professed Apollo-era enthusiast, Reibaldi serves as president of the Moon Village Association, a Vienna-based non-governmental organization that advocates for the establishment of a permanent human presence on the Moon. Since those Apollo-era days of his youth, a lot has changed, Reibaldi says, and the case for a lunar settlement now makes much more sense than it did 50 years ago.

“In the 1960s, going to the Moon was a political goal,” Reibaldi told IFLScience. “It was a prize in the competition between the United States and the Soviet Union. But when the Americans got there, they got the impression that the Moon was totally inhospitable and didn’t have too many prospects. So, it was left alone.”

Six crewed missions landed on the Moon between 1969 and 1972. Overall, the 12 American astronauts who walked (or bounced) on the Moon collected more than 380 kilograms (838 pounds) of lunar rocks and soil. In the subsequent decades, analyses of these samples with modern instruments, as well as observations made by later lunar orbiters, revealed that the Moon might not be such a lost cause after all.

In 2012, the Indian probe Chandrayaan-1 found evidence of water ice in the permanently shaded regions of the enormous craters that pockmark the Moon’s polar regions. That discovery put the idea of a permanent lunar settlement back on the table. With water ice inside the craters, humans could exist on the Moon without having to bring everything they need for survival from Earth, a costly – and in the long-term, unsustainable – solution.

“Water is called the gold of space,” Reibaldi explained. “If you have water, you can make oxygen from it, you can use it for the crew or to grow plants. You can even make propellant from it.”

But more has changed since the Apollo era than our knowledge of the presence of water on the Moon, adds Reibaldi. The leaps and bounds in the development of technology in recent decades mean that a whole range of countries, as well as private companies, now have plans to land rovers and experiments on the Moon.

“The exploration and utilization of the Moon now has a larger appeal because there is a potential for developing a market,” Reibaldi says. “And thanks to the technological development that we have seen, it is now possible to go to the Moon with much smaller budgets than was the case in the 1960s.”

A busy decade ahead

In parallel to the US-crewed Apollo landings, the Soviet Union landed eight robotic probes on the Moon in the 1960s and 1970s. China joined the Moon Club in 2013 with its Yutu rover and later achieved a first by placing Yutu 2 on the Moon’s far side. India made headlines last year when its Chandrayaan-3 mission, in a historic first, placed the Vikram lander and its companion rover Pragyan on the Moon’s South Pole – the area with promising water resources.

Japanese start-up iSpace made an unsuccessful attempt to soft-land on the Moon last year. Another Japan-led effort, the SLIM mission (for Smart Lander for Investigating Moon) by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, is to attempt a touchdown on January 19.

An entire fleet of NASA-supported private landers carrying all kinds of experimental technologies needed for human habitation on the Moon is lined up for launch in the next two years.

If all goes well, these companies, Reibaldi stated, will one day be providing services to future government-funded Moon stations. By 2075, a thriving ecosystem may exist on the Moon, consisting of multiple bases at various sites – not just at the South Pole, but on the mysterious far side as well. Local resource utilization workshops will be supplying occupants of these stations with water and construction materials, as well as titanium and aluminum to make spacecraft parts. Launches to Mars may be taking place from the Moon in that timeframe, and high-tech farms will ensure a grown-on-the-Moon food supply.

“The turning point is going to be the first baby born on the Moon,” Reibaldi added. “I do believe that within the 2075 timeframe, there will be a baby born on the Moon. And that will demonstrate whether humankind can survive independently of Earth.”

The roadmap to the Moon

Professor Ian Crawford, a planetary scientist and astrobiologist at London’s Birkbeck College, has more modest expectations. By 2075, he foresees a permanently inhabited station like those now present in Antarctica, and possibly a small lunar hotel for wealthy space tourists run by a private company like Amazon, SpaceX, or Virgin Galactic.

“I think there will be a permanently crewed station on the Moon by 2075 with crews working in shifts perhaps every six months like they do on the International Space Station now,” Crawford told IFLScience. “I do think there will probably be a permanent human presence, supporting a diverse range of scientific activities, supported somewhat by locally sourced lunar materials – like water and oxygen.”

NASA is spearheading Western efforts to return humans to the Moon’s surface. Fifty-three years after the final Moon landing – that of Apollo 17 in December 1972 – the Artemis 2 mission was scheduled to make a crewed flyby of the Moon in 2024, with Artemis 3 landing the following year. Crawford, however, thought the timeline to be a little optimistic.

“In order to land people on the Moon, which NASA hopes to do with the Artemis 3 mission in 2025, you need to have a vehicle that can land there and then return to orbit. Something like the lunar module from the Apollo era,” Crawford says. “But currently, no such vehicle exists. NASA contracted SpaceX to develop this landing module, based on the Starship, but the Starship hasn’t even successfully launched from the Earth yet. So, I am personally sceptical that it can be done by 2025. It can probably be achieved by the end of this decade.”

Crawford was quickly vindicated this week, with NASA announcing that the Artemis 2 mission has been postponed to September 2025. The next landing, NASA envisions, could take place just one year later.

In 2025, NASA also intends to launch the first building block of the future Moon-orbiting space station – the Lunar Gateway, which will provide a base for future Artemis missions to explore the lunar surface from. By the late 2030s, 10 crewed Artemis missions may have taken place. Beyond that, the roadmap gets hazy.

In its Plan for Sustained Lunar Exploration and Development, published in 2020, NASA introduced an early concept of the Artemis Base Camp in the lunar South Pole region. No date has been attached to this plan, which is much more modest than Reibaldi’s lunar village vision for 2075. The Base Camp, a gradually expanded outpost, could support crews of up to four astronauts for visits lasting a week or two at first, which could gradually be extended up to two months.

The case for science

Xiaochen Zhang, a planetary scientist and PhD researcher in lunar resource utilization at the European Space Resources Innovation Center (ESRIC) in Luxembourg, agrees with Crawford that humankind’s expansion on the Moon will not be fast-paced.

“Fifty years might seem like a long time, but in the field of space exploration, it's probably not that long,” Zhang told IFLScience. “Developing missions, testing technology, it all takes a long time. But I think that in 50 years there should be at least some sort of a basic lunar base. There will hopefully be scientists studying on the Moon, doing experiments, and some sort of regular transportation between Earth and the Moon as well.”

Zhang is currently developing a machine that could one day process lunar dust directly on the Moon and turn it into usable construction material that could be used in 3D printing. Her true passion, however, is science. A trained geologist, she likes the idea of participating in a lunar research trip one day.

“I would love to study geology in situ on the Moon,” she says. “Like taking samples during the day, then come back to the station and analyse them right there on the Moon.”

Doing science directly on the Moon is a big draw, Crawford agrees. Just like Antarctic research stations, crewed outposts on the Moon would enable major leaps in humankind’s understanding of the cosmos.

“There is a lot of science to be done on the Moon: lunar geology, astronomy from the Moon, life sciences on the Moon,” said Crawford. “It would be greatly facilitated if there was a permanent supporting scientific infrastructure. A lunar base would provide that.”

At the Astronomy from the Moon conference co-organized by Crawford in London last year, astronomers introduced a whole range of concept facilities that could one day operate on the Moon. A gravitational wave detector, a next-generation infrared telescope that would succeed JWST, or a radio telescope on the Moon’s far side could all become part of the lunar science infrastructure by 2075.

Unlocking the invisible universe

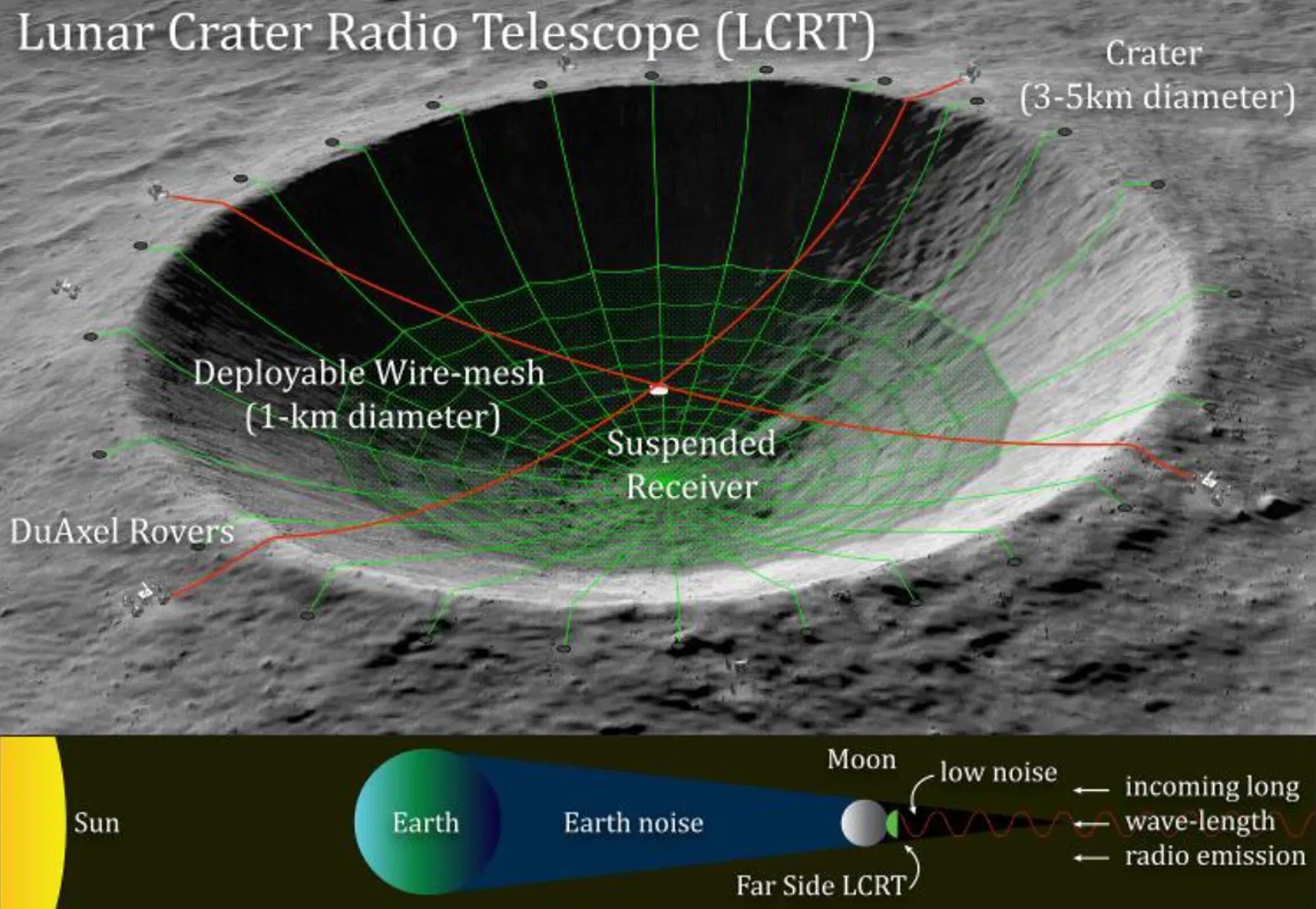

According to Crawford, the lunar radio telescope is at the top of the wishlist of many astronomers. The far side of the Moon, he explains, is the best place for radio astronomy in the entire Solar System.

“That’s because the far side of the Moon never sees the Earth, so it's permanently shielded from all of the artificial radio noise that the Earth produces,” Crawford says. “And of course, during the lunar night on the far side, it doesn't see the Sun either. And the Sun is the second most radio-noisy thing in the Solar System after the Earth. So, for two weeks every month, the far side of the Moon is totally radio-quiet. There's no background interference of any kind.”

Radio astronomy is the branch of astronomy that studies radio waves coming from stars, planets, galaxies, black holes, and other sources in the universe. Radio waves are the type of electromagnetic radiation with the longest wavelengths.

On Earth, humans rely on radio waves for a whole range of indispensable applications, including TV and radio broadcasting, radar sensing, navigation systems, and wireless computer networks.

The Earth’s best radio telescopes, such as the Square Kilometre Array, currently under construction on sites in Australia and South Africa, are protected by radio quiet zones where no radio equipment is allowed. Still, these super sensitive antenna arrays, spanning areas hundreds of kilometers across, are blind to an entire portion of the cosmic radio spectrum, which is blocked out by the Earth’s atmosphere.

“Wavelengths longer than about 20 metres don't get through the Earth's ionosphere [a part of the atmosphere] from outside,” Crawford explains. “So, long-wavelength, low-frequency radio astronomy is the one last big unexplored part of the electromagnetic spectrum in astronomy because we can't do it from the surface of the Earth.”

Astronomers know that a whole range of new discoveries are waiting to be made in this spectral range. One of the most exciting areas of research is what astronomers call the Cosmic Dawn signal, radiation emitted by the hydrogen gas that filled the universe in the first hundreds of millions of years after the Big Bang.

In 2020, NASA unveiled a concept for the Lunar Crater Radio Telescope that could be built in a small crater on the Moon’s far side.

A lunar war?

But the US and their allies are not the only ones eyeing the Moon. In 2021, Russia and China announced separate plans to establish a permanent station on the Moon. Neither country has signed the Artemis Accords, a non-binding multilateral agreement drafted by the US government to ensure peaceful international cooperation around lunar exploration and settlement.

The US Congress banned NASA from cooperating with China on space projects in 2011, due to fears of industrial espionage and security concerns. The partnership with Russia, which has formed the basis of the International Space Station collaboration since the 1990s, has suffered a major blow due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The possibility that Earthly geopolitical conflicts may spill over onto the Moon is a concern of many experts, says Crawford. He describes a scenario akin to the territorial dispute between China and its neighbors over the South China Sea, which is one of the world’s main flashpoints for armed conflict.

“We really don’t want a situation when we would have a US-led Artemis Accords Moon base and a Russia-China Moon base within a few hundred meters of each other near the lunar South Pole,” Crawford says. “Unfortunately, this is a trajectory that we seem to be on currently and I think this is a recipe for disaster.”

But Crawford hopes that not all is lost. Although neither Russia nor China are signatories to the Artemis Accords, both countries have signed the Outer Space Treaty, which prohibits states from appropriating celestial bodies or their parts.

Despite the current tensions, the space agencies of Russia and China are represented in the International Space Exploration Coordination Group, a global space exploration forum founded in 2007 with the goal of fostering international cooperation in space exploration.

Despite the enormous technical tasks that need to be solved to make a permanent human presence on the Moon possible, Crawford thinks that the greatest challenge lies in ensuring that the endeavor is a peaceful one.

“I do think that getting the politics right is more important than the technical aspects,” says Crawford. “I can see these will clearly be possible by 2075. It's getting the politics and the regulator regime in place that is the real challenge.”

![An artist’s concept looks down into the core of the galaxy M87, which is just left of centre and appears as a large blue dot. A bright blue-white, narrow and linear jet of plasma transects the illustration from centre left to upper right. It begins at the source of the jet, the galaxy’s black hole, which is surrounded by a blue spiral of material. At lower right is a red giant star that is far from the black hole and close to the viewer. A bridge of glowing gas links the star to a smaller white dwarf star companion immediately to its left. Engorged with infalling hydrogen from the red giant star, the smaller star exploded in a blue-white flash, which looks like numerous diffraction spikes emitted in all directions. Thousands of stars are in the background.]](jpg/jet-m.jpg)