In the latest move towards more sustainable construction, engineers at MIT have come up with an ingenious way of producing 3D-printed, reusable bricks – but the material they’ve chosen might just surprise you. They’re made of glass, but their clever construction means they’re every bit as good as concrete, with better green credentials.

“Glass as a structural material kind of breaks people’s brains a little bit,” said researcher Michael Stern in a statement. Stern is founder and director of Evenline, the MIT spinoff that developed the custom 3D printing technology that was used to make the bricks.

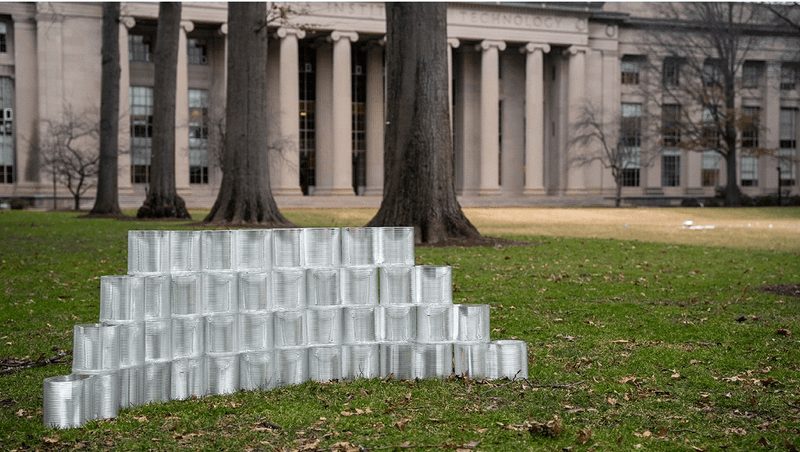

It’s true that when we think of glass, we tend to think of words like “fragile” and “breakable” – not usually desirable qualities in a structural material. However, printing each brick in multiple layers gives a result that, in tests, held up to a similar amount of pressure as a concrete block. They’re also shaped like a figure of eight, meaning multiple bricks can be interlocked just like LEGO, but with the possibility of building curved shapes.

“I found the material fascinating,” said Stern, recalling when he had first learned about glassblowing as an undergraduate. “I started thinking of how glass printing can find its place and do interesting things, construction being one possible route.”

As colleague Kaitlyn Becker, an assistant professor at MIT who was also an undergrad with Stern, points out, “Glass is a highly recyclable material.” Almost infinitely so, as it turns out. Stern and Becker teamed up, along with colleagues at MIT and Evenline, to investigate the possibility of producing glass bricks that were as sturdy and stackable as their concrete equivalents.

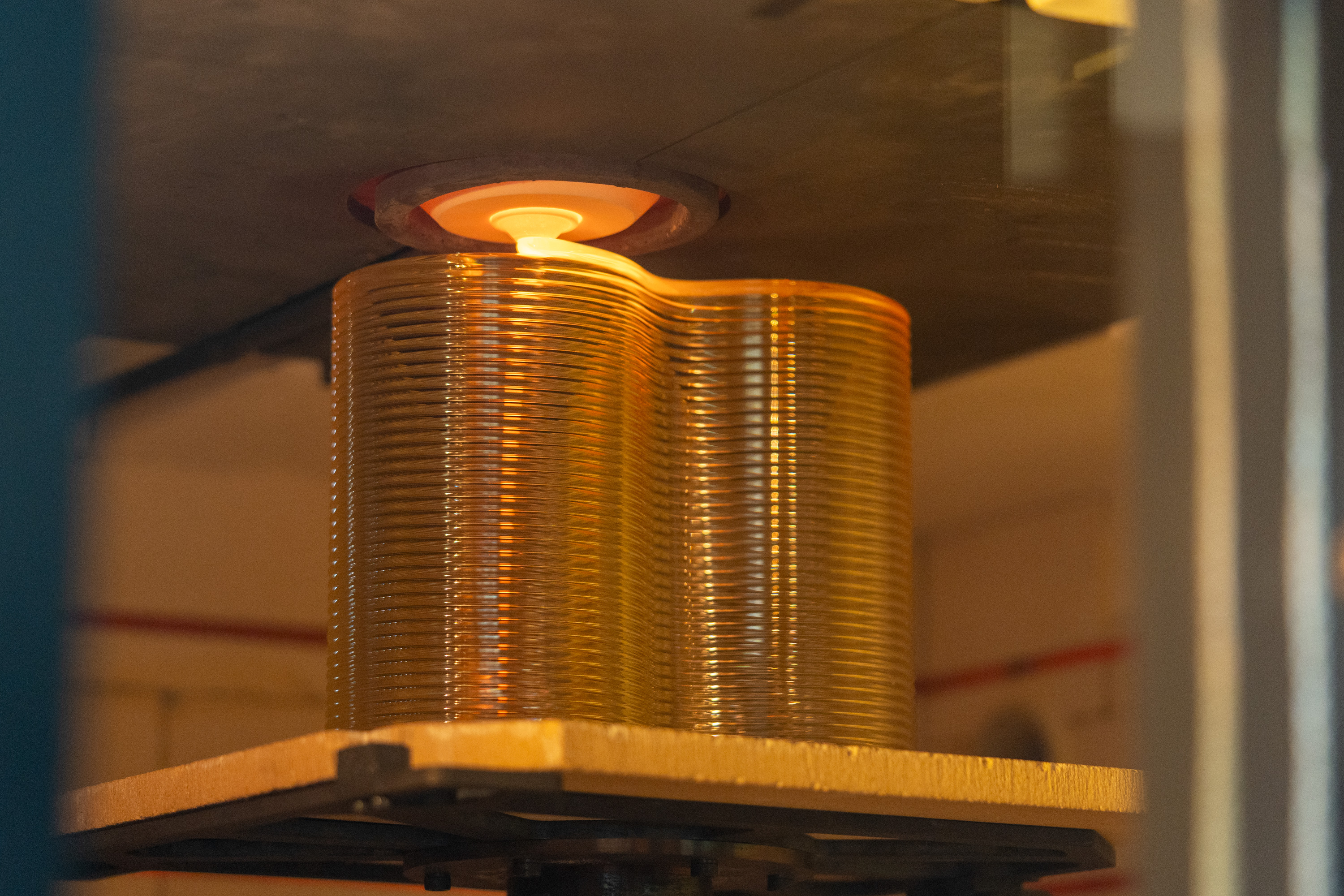

The system can use glass bottles – so the recycling is baked right in – which are crushed and melted down for the printer to deposit layer by layer. The strongest prototype bricks were constructed mostly from glass with a separate interlocking feature that uses pegs, much like the oh-so-painful studs on a LEGO brick. These interlocking elements currently need to be made from a different material, but when this is removed the bricks themselves can be repositioned or melted down and reused.

This is an example of circular construction, which seeks to minimize the need for new building materials wherever possible to help reduce the greenhouse gas emissions associated with the construction industry.

The team built a curved wall to show the potential of their innovation, and they’re now aiming even higher.

“We’re thinking of stepping stones to buildings, and want to start with something like a pavilion – a temporary structure that humans can interact with, and that you could then reconfigure into a second design,” Stern said. “And you could imagine that these blocks could go through a lot of lives.”

“We’re showing this is an opportunity to push the limits of what’s been done in architecture.”

The study is published in the journal Glass Structures & Engineering.