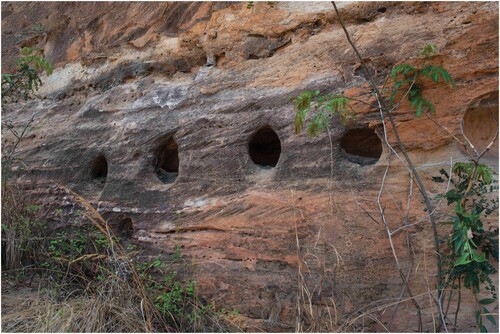

Around the first millennium CE, an enigmatic group of people living in southern Madagascar carved large chambers and hollows into the rock of a cliff face. For decades, the terraces and architecture at this site puzzled archaeologists as it is like nothing else found in Madagascar or elsewhere along the nearby East African coast. Who created these rock niches, and when did they arrive on the island?

According to a new study, the mysterious people may have been a Zoroastrian community living in Madagascar around 1,000 years ago.

A strange site

The rock terraces are located at a site called Teniky (also known as "Tenika"), an inland location at the heart of the Isalo National Park, in central-southern Madagascar. The rock structures at the site have been known for over 100 years, but there has been little sustained archaeological research of them over this time.

This is partially due to their remote location. In order to reach them, excavation teams have to hike 20 km (12 miles) across difficult terrain with steep canyons. As study author Professor Guido Schreurs explained to Phys.org, “All the equipment and food has to be carried to the site. It also has to be mentioned that archaeological research in Madagascar always requires collaboration with local institutions and authorizations from different ministries (which is sometimes challenging).”

In the early twentieth century, French naturalists called Alfred and Guillaume Grandidier suggested the rock niches at Teniky may have been carved by Portuguese sailors stranded on island in the 16th century. These sailors, so the idea goes, carved into the cliffs to build shelters while they search for a viable port. This earnt the area the name “Grotte des Portugais”.

Later, in the 1963, archaeologists Ginter and Hébert rejected this idea as the hollow niches would have taken a too much effort to carve. They conducted a trench excavation around the area. Although they did not recover and artifacts at the site, they did uncover Chinese jar sherd dating to the 16th century on the slopes of the cirque where Teniky is situated.

In 2019, further research using high-resolution satellite images showed that the archaeological site was far larger than previously thought. The images revealed many terraces and linear and rectangular structures that had been overlooked. These new findings promoted further investigation from Schreurs and his colleagues.

The field surveying and excavation were conducted for structures at sites known as the Grande Grotte and the Petit Grotte, two rock-cut chambers supported by large stone pillars that also have stone benches carved into the walls.

The team found dozens of other circular and rectangular stone niches across the rest of Teniky, some of which had circular recesses which may have been closed off by wooden or stone slabs. They also discovered over 30 hectares of man-made terraces, stone basins, circular and rectangular stone structures, rock-cut conglomerate boulders, and ceramic sherds.

The enigmatic people

Analysis of charcoal and ceramic sherds recovered during the excavation, the site was occupied around the 10th and 12th century CE. The sherds were not created locally, suggesting whoever lived there had connections to the Indian Ocean trade network. Moreover, some of the sherds were Southeast Asian in origin, dating to the 11th and 13th centuries, while others came from China in the 11th and 14th century.

This discovered eliminated the idea that Portuguese sailors created the structures, as the first Portuguese ships did not arrive in the Indian Ocean until 1498.

So who did build them? Schreurs and colleagues cast their analytical nets a little wider. The Malagasy population are thought to have genetic, linguistic and cultural ties to Austronesia, India, Arabia, and Persia, so this seemed like a place to start.

“While reviewing the literature, I was struck by the mention of rock-cut niches in various shapes and sizes in many regions throughout Iran, including the Fars region,” Schreurs explained.

“I did find photographs of these niches in several publications, and there were niches with recesses—just as at Teniky—indicating that they were initially probably closed off by a wooden or stone slab; these niches most likely served as bone ossuaries."

This led him to hypothesize that the mysterious population at Tenkiy could have had Zoroastrian origins.

"Most archaeologists associate the niches in Iran with Zoroastrian funeral rites. So, that's how the initial potential link with Zoroastrian practices came up. At the same time, from primary historical sources, we know that the coastal region of Iran (e.g. the port town of Siraf) was involved in maritime trade since Sassanid times and that ships from Siraf were sailing the oceans as far as China and East Africa.”

The trade connections continued into the 7th century, when Arabs conquered Persia and Islam was imposed. It is well known from historical sources that, up until the 10th century, communities of Muslims, Jews, Christians, and Zoroastrians coexisted in these Iranian ports.

Although this idea is only a hypothesis at this time, the stylistic similarities of the stone basins and tables at Teniky to those for Zoroastrian rituals are quite compelling.

The bones of a problem

Although the case for a Zoroastrian community at Tenkiy looks good, there is one problem: Zoroastrians believed that the dead should not be buried straight away, because the body was seen to be polluting. As such, bodies were left on display above ground in stone niches called “dakhmas” in the Persian Pahlavi language. Over time, natural exposure and animals would reduce the body to bones which were then transported into small circular niches called “astōdans” that could be closed off.

But to date, no bones have been recovered from Teniky. If the smaller holes in the cliffs were meant to ossuraries, then you would expect some evidence of bones, especially teeth, to remain at the site. However, this may not blow the idea out of the water, as it is possible any remains left in these holes have been removed by subsequent people living in the area.

So the Zoroastrian hypothesis is still valid. The historical and archaeological evidence does seem to indicate that a community of from this religion did arrive on Madagascar in the first millennium. But if this is the case, then why did they abandon the site?

Schreurs and colleagues will return to the site again in 2025 for further excavations. They plan to conduct a Lidar survey to find any structures that have so far been overlooked. Perhaps they will find more answers to add flesh to the bones of the mysterious people who lived there a thousand years ago.

The study is published in the journal Azania.