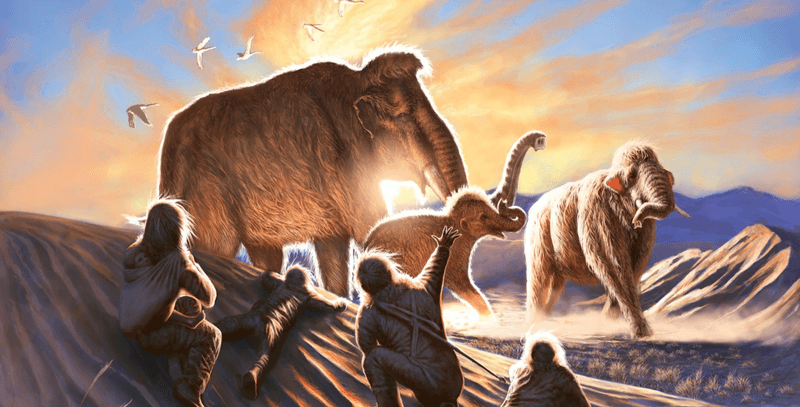

Using little more than a tusk, scientists have pieced together the lifetime travels of a single woolly mammoth that wandered North America more than 14,000 years ago.

Starting life in the western Yukon, the mammoth traveled hundreds of kilometers through northwestern Canada before arriving at her final resting place, an early human settlement in present-day Alaska. It seems there’s little doubt that this venturing mammoth was slaughtered by a hungry group of hunter-gatherers.

The international team of researchers from McMaster University, the University of Alaska Fairbanks, and the University of Ottawa chronicled the epic journey by studying a mammoth tusk using ancient DNA and isotopic analyses.

Isotope analysis relies on the principle of “you are what you eat.” The technique is capable of providing precise insights into an animal's life – such as their diet, geographic origin, and migration patterns – by looking at the concentration of certain stable isotopes within their tissues that were picked up from their surrounding environment.

The complete tusk belonged to a woolly mammoth that was recently named “Élmayuujey’eh”. It was unearthed alongside remains of a juvenile and a baby mammoth at Swan Point, an archaeological site that’s home to the earliest evidence of humans in Alaska.

The analysis of the tusk showed that the mammoth was an adult female who was around 20 years old when she died some 14,000 years ago. This was a critical window of time when the last remaining woolly mammoths lived alongside the region’s first human inhabitants for at least 1,000 years.

The mammoth spent much of her life in a relatively small area of the Yukon. However, as she grew older, she migrated over 1,000 kilometers (621 miles) in just three years before settling in the midst of Alaska.

Altogether, this information strongly suggests that the mammoth was killed by human hunter-gatherers.

“She was a young adult in the prime of life. Her isotopes showed she was not malnourished and that she died in the same season as the seasonal hunting camp at Swan Point where her tusk was found,” Matthew Wooller, senior author, director of the Alaska Stable Isotope Facility, and a professor at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, said in a statement.

The researchers think it’s a reasonable bet that the two young mammoths found near her remains were her children. It’s believed mammoths behave much like modern elephants, with females and young-uns living in close-knit matriarchal herds and mature males traveling solo.

Significantly, the remains of mammoths have been found at three other archaeological sites within just 10 kilometers (6.2 miles) of Swan Point. This led the researchers to conclude that this region was a meet-up point for at least two closely related, but different herds.

“This is more than looking at stone tools or remains and trying to speculate. This analysis of lifetime movements can really help with our understanding of how people and mammoths lived in these areas,” added Tyler Murchie, a recent postdoctoral researcher at McMaster University's Department of Anthropology.

The study is published in the journal Science Advances.