It seems like every couple of months there’s a new headline claiming “mammoth cloning is just around the corner”. While it will still be many years before this extinct species is roaming the tundras of Siberia once again, a new study could help this dream edge closer to reality.

Writing in the journal Scientific Reports, scientists from Kindai University in Japan have documented mammoth nuclei showing “signs of biological activity” after being transplanted into mouse oocyte cells.

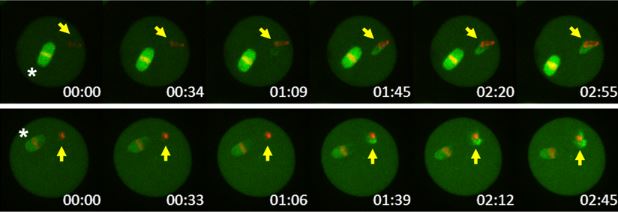

They started by taking samples of bone marrow and muscle tissue from the leg of a mammoth that had been frozen in Siberian permafrost for 28,000 years. Analysis revealed that the mammoth cells still contained relatively undamaged nucleus-like structures, which were extracted and then transferred into living mouse oocytes, cells found in ovaries that can undergo genetic division to form an egg cell.

After nuclear transfer, mouse proteins were loaded onto the mammoth cell nucleus and some started to show signs of nuclear reconstitution, hinting that ancient mammoth remains might still possess partially active nuclei.

Five of the cells even displayed stages of activity that occur immediately before cell division, although the study notes that “the full activation of nuclei for cleavage was not confirmed.”

Kei Miyamoto, study author from the Department of Genetic Engineering at Kindai University, told Nikkei Asian Review that the research was a “significant step toward bringing mammoths back from the dead”, however, he conceded that it's still early days.

"We want to move our study forward to the stage of cell division," Miyamoto added, but “we still have a long way to go."

The subject of the study was a mammoth named “Yuka”, an incredibly well-preserved individual that was found near the mouth of the Kondratievo River in Siberia over the summer of 2010.

Most mammoths died out between 14,000 and 10,000 years ago, towards the end of the last glacial period. However, one isolated population managed to survive on Wrangel Island in the Arctic Ocean until around 4,000 years ago, hundreds of years after the construction of the Great Pyramid of Giza.

Talk of mammoth de-extinction has been whirling around for decades. The steps have been slow and cautious, but steady. Over the past few years alone, scientists have managed to sequence complete mammoth genomes, and have inserted mammoth genes into the genome of an elephant.