Evidence has been revealed of a city existing 5,400-4,900 years ago in what is now Morocco, that its discoverers claim was the era’s largest in Africa outside of the Nile Basin. There are signs the region had extensive trading links with settlements across the Strait of Gibraltar in Iberia, and its influence may well have stretched much further afield around the Mediterranean.

Morocco houses what some consider the oldest fossils of our species, Homo sapiens, as well as the oldest shell beads and a shift in stone technology. The Maghreb, the region that combines Morocco with areas east as far as Libya, was home to Carthage, the power that most threatened the Roman Republic.

However, between 6,000 and 3,000 years ago, there is a vast hole in our knowledge of the area. Perched as the Maghreb is between the Sahara Desert and the ocean, it’s possible to wave this away by imagining the coastal strip becoming temporarily too arid to support many people. However, Professor Cyprian Broodbank of Cambridge University has been resisting this idea for a long time.

"For over thirty years I have been convinced that Mediterranean archaeology has been missing something fundamental in later prehistoric north Africa,” Broodbank said in a statement. “Now, at last, we know that was right, and we can begin to think in new ways that acknowledge the dynamic contribution of Africans to the emergence and interactions of early Mediterranean societies.”

Broodbank has been conducting a dig at a site known as Oued Beht with researchers from Moroccan and European institutions. Now, they are reporting that in around 3000 BCE, this was a city similar in size to Troy during its Bronze Age peak.

“This is currently the earliest and largest agricultural complex in Africa beyond the Nile corridor,” the authors write.

Besides many of the items familiar from other Neolithic civilizations, the archaeologists have dug up pits similar to those found in what is now Spain, thought to be used either to store food or for waste disposal. The Spanish pits had already provided major hints that the inhabitants of the era had an African trading partner in the form of ivory and ostrich eggs, neither of which they could have obtained locally.

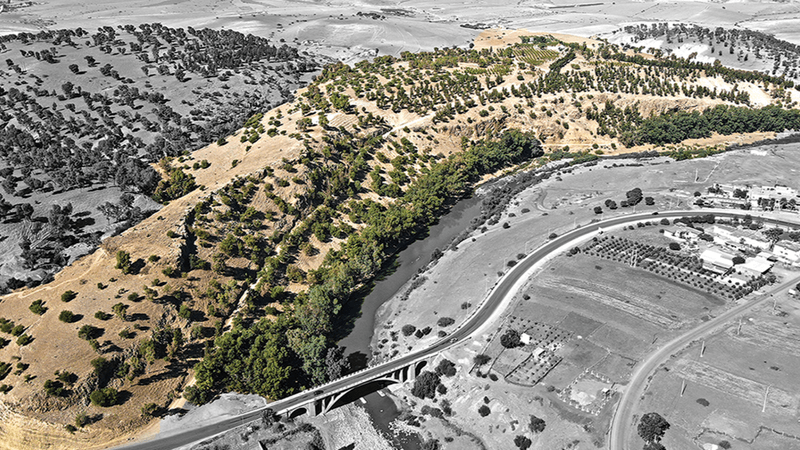

Oued Beht lies on a river of the same name about 100 kilometers (62 miles) inland of Rabat. The Atlantic Ocean would have been fairly accessible downstream, but reaching the Mediterranean other than by passage through the Strait would have required crossing the Atlas Mountains, which may have impeded interactions with most of the ancient world. Nevertheless, the similarities with Iberian sites of the same era make it likely there was considerable interchange, perhaps indicating the development of ships capable of reliably sailing the open ocean.

Many stone axes and the remains of stone walls were found at Oued Beht in the 1930s, and more than a thousand axes have been found there since. However, it took 70 years for systematic archaeology to start in the area.

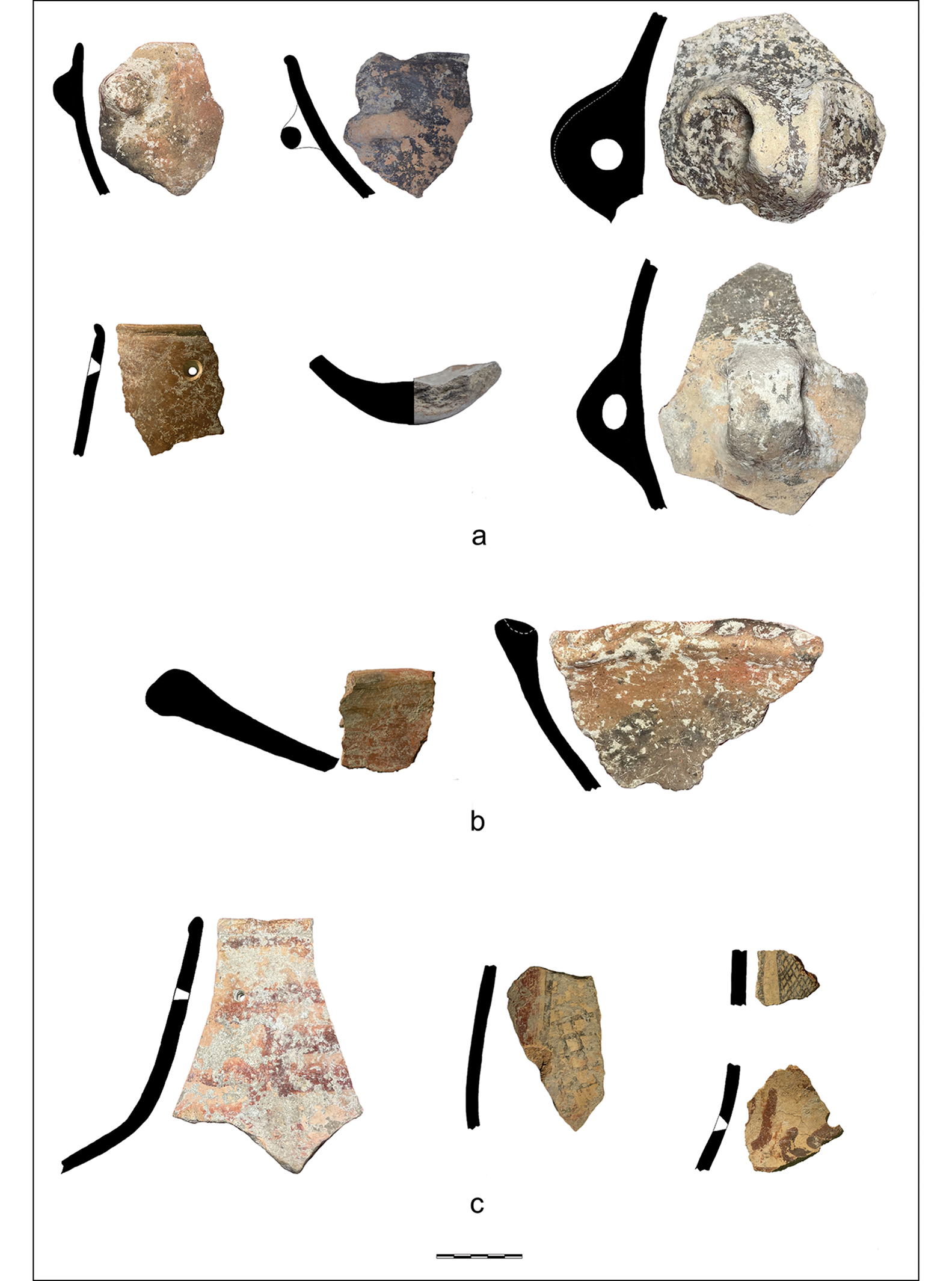

This has now revealed an abundance of pottery – some heavily decorated – and stone tools unmatched in Africa outside the Nile Valley. There are also signs of domesticated goats, sheep, cattle, and pigs. No tools for harvesting crops have been found, but the authors think this indicates collection with bare hands, rather than a lack of cereal production, given the large grinding stones that were found.

The objects overwhelmingly date to a 500-year period, suggesting much less intensive use of the site before and after.

"It is therefore crucial to consider Oued Beht within a wider co-evolving and connective framework embracing peoples on both sides of the Mediterranean-Atlantic gateway during the later fourth and third millennia BC,” the authors write. “For all the likelihood of movement in both directions, to recognize it as a distinctively African-based community that contributed substantially to the shaping of that social world."

The study is published in Antiquity.