Tulip trees have a category-busting wood structure unlike anything scientists have seen before. Although more research is needed, this could enable them to store carbon more efficiently than other species, which might come in very useful.

Tulips do not of course grow on trees, although during the infamous mania someone might have spread claims they do. However, the two surviving members of the ancient Liriodendron genus are known as the tulip tree and Chinese tulip tree and can grow to 30 meters (100 feet) high.

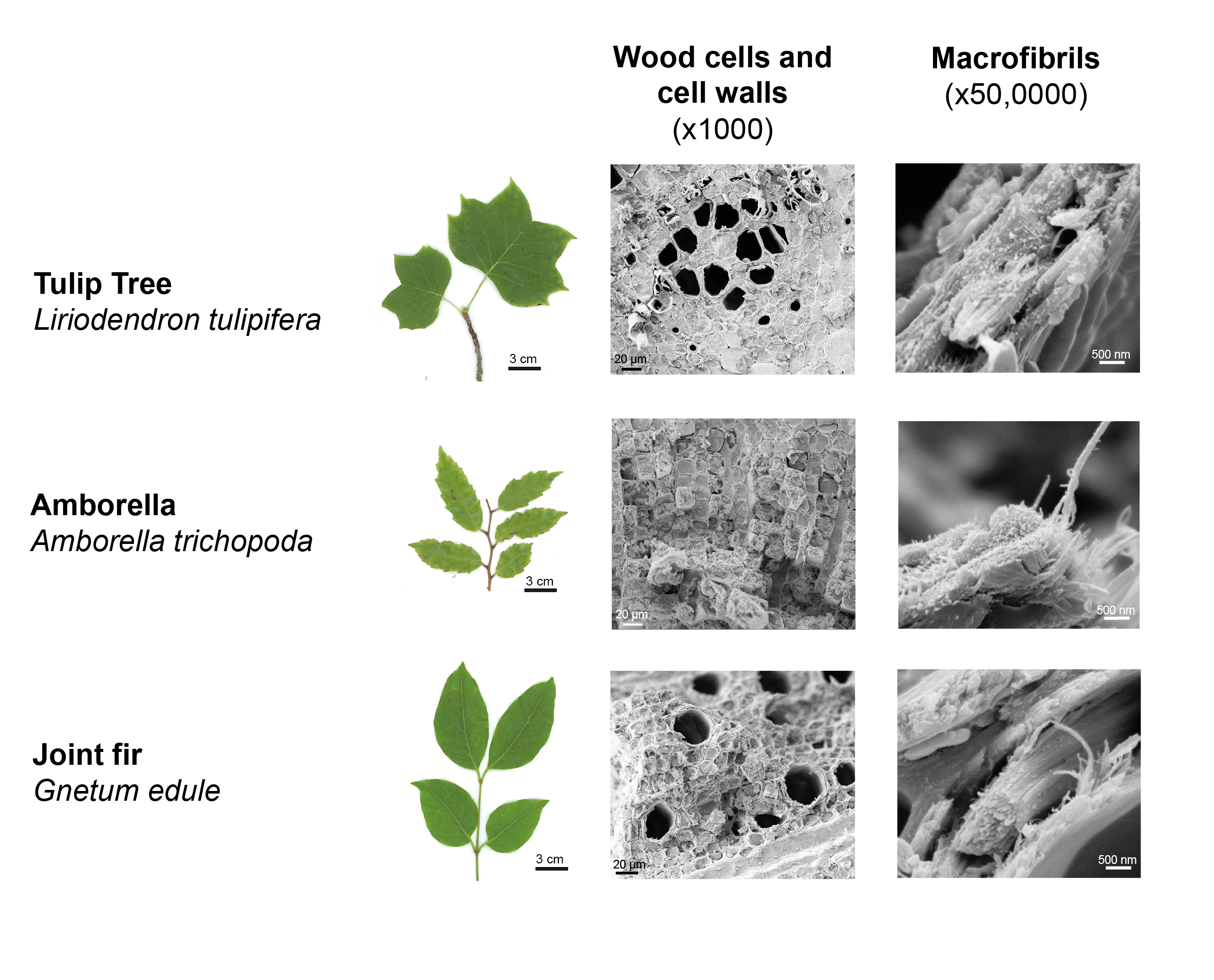

Dr Jan Łyczakowski of Jagiellonian University led a team that put tulip tree wood under low temperature scanning electron microscope so they could study it in close to its natural state. They found the trees’ nanostructure was unlike anything seen before. Trees’ secondary cell walls contain long parallel fibers arranged in layers known as macrofibrils, which are primarily made of smaller cellulose fibers. They provide most of the bulk and strength of wood, growing after the thin and flexible primary cell walls, and make up the largest single store of carbon among organisms, living and dead.

“We show Liriodendrons have an intermediate macrofibril structure that is significantly different from the structure of either softwood or hardwood. Liriodendrons diverged from Magnolia Trees around 30-50 million years ago, which coincided with a rapid reduction in atmospheric CO2. This might help explain why Tulip Trees are highly effective at carbon storage,” Łyczakowski said in a statement.

Hardwood trees have small macrofibrils, and the team think the tulip trees' larger structure might be why they can grow faster than hardwoods. Łyczakowski noted that both tulip trees have already been recognized as efficient carbon absorbers. For the trees, this would have been a useful trait when carbon dioxide was in short supply, but from our perspective it could be attractive for the opposite reason. “Some east Asian countries are already using Liriodendron plantations to efficiently lock in carbon, and we now think this might be related to its novel wood structure,” Łyczakowski said.

Locking carbon in wood has limitations when trees burn or die of old age, particularly if they’re not part of a sustainable forest, which usually requires mixed species. However, even a temporary carbon soak that gives us time to work out longer term solutions has appeal.

Łyczakowski thinks the significance of the work extends beyond two tree species that survived on opposite sides of the Pacific Ocean when the rest of their genus died out. “Despite its importance, we know little about how the structure of wood evolves and adapts to the external environment,” he said. For this reason, he collaborated with Cambridge University Botanic Garden on a survey of the wood structure of 33 species, which the authors think is the largest of its type ever conducted.

“We made some key new discoveries in this survey – an entirely novel form of wood ultrastructure never observed before and a family of gymnosperms with angiosperm-like hardwood instead of the typical gymnosperm softwood,” Łyczakowski said in reference to two gnetophyte species. Although not related to hardwoods, by convergent evolution the gnetophytes the have found a similar small macrofibril structure best suits their environmental niche. Liriodendrons and gnetophytes aside, all the hardwoods studied had macrofibrils with similar diameters, about half those of softwoods.

The study is published in the wonderfully named journal New Phytologist.